The Complete History of Plan Checking: From Ancient Babylon to AI-Powered Review

Explore 4,000 years of building code evolution—from Hammurabi's death penalty for faulty construction to today's AI-powered plan review systems. Discover how fires, disasters, and innovation shaped the profession that keeps our buildings safe.

Every building you walk into—your home, your office, the hospital where your children were born—stands because someone checked that it was built safely. The profession of plan checking, though rarely celebrated, has quietly protected humanity for millennia.

This is the story of how we went from ancient kings executing negligent builders to sophisticated AI systems reviewing thousands of pages in minutes. It's a story written in stone tablets, inked on blueprints, and now encoded in algorithms—a continuous thread of human ingenuity dedicated to one simple goal: keeping people safe.

"If a builder builds a house for someone, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built falls in and kills its owner, then that builder shall be put to death."

These words, carved into black diorite nearly 4,000 years ago, represent humanity's first attempt to codify building safety. The stakes were clear: build it right, or pay with your life.

Part I: Ancient Origins

1754 BC – 1600 AD

The World's First Building Code

In the sun-baked city of Babylon, King Hammurabi faced a problem familiar to any modern building official: how do you ensure builders construct safe buildings without personally inspecting every mud brick?

His solution was elegantly brutal. Around 1754 BC, Hammurabi commissioned 282 laws to be inscribed onto twelve massive stone tablets. Among them, clauses 229 through 233 established what historians recognize as the world's first building regulations.

The code didn't specify how to build—it specified what happened when you built poorly. This distinction matters: rather than prescribing construction methods, Hammurabi created accountability through consequences.

Hammurabi's Building Laws: The Original Code Compliance

If a house collapses and kills the owner → Builder is executed

If it kills the owner's son → Builder's son is executed

If it kills a slave → Builder must replace the slave

If it destroys property → Builder must restore it at own expense

These laws established three principles that survive in modern building codes: reciprocity (punishment fits the crime), accountability (builders bear responsibility), and incentives (severe penalties discourage negligence).

Roman Engineering and the Birth of Building Officials

A thousand years after Hammurabi, the Romans advanced construction regulation in ways that still echo today. Their innovations weren't just architectural—they were administrative.

Rome introduced the concept of the Aedile—elected officials responsible for maintaining public buildings, regulating construction, and ensuring street cleanliness. These weren't engineers; they were bureaucrats with enforcement power. Sound familiar? The Aediles were the world's first building officials.

But it took disaster to truly advance Roman building codes. On July 19, 64 AD, the Great Fire of Rome burned for six days, destroying 10 of Rome's 14 districts. Emperor Nero, despite his notorious reputation, responded with surprisingly modern regulations:

- •Material requirements: Buildings must use fireproof stone and brick, not timber

- •Height limits: Structures capped at 70 Roman feet (approximately 21 meters)

- •Street widths: Minimum widths mandated to prevent fire spread

- •Water access: Buildings required to have firefighting equipment accessible

This pattern—disaster followed by regulation—would repeat throughout history. Every major building code advancement came at a terrible price in human lives.

Part II: The Birth of Modern Building Codes

1666 – 1900

The Great Fire of London (1666)

On September 2, 1666, a fire broke out in Thomas Farriner's bakery on Pudding Lane. What began as a small kitchen fire would become one of history's most consequential disasters—not for its death toll (remarkably low at perhaps six confirmed deaths), but for what it destroyed and what rose from the ashes.

Over four catastrophic days, the fire consumed 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, St. Paul's Cathedral, and most of the buildings of the City authorities across 436 acres—roughly 80% of the City of London.

King Charles II's response was revolutionary. The London Building Act of 1667 became the first comprehensive building code in the English-speaking world, establishing principles we still follow today:

Material Standards

All buildings must be constructed of brick or stone—timber frames were banned from exteriors

Building Classification

Four classes of buildings based on location and importance, each with specific requirements

Wall Thickness

Minimum wall thicknesses specified based on building height and class

Party Walls

Fire-resistant walls required between adjoining buildings to prevent fire spread

The Great Chicago Fire (1871)

On October 8, 1871, Chicago learned London's lesson the hard way. A fire—legend says it started in Catherine O'Leary's barn—swept through a city built almost entirely of wood.

The statistics are staggering: 17,500 buildings destroyed, 300+ people killed, 100,000 left homeless—one-third of the city's population. Property damage exceeded $200 million (roughly $4.7 billion today).

But from these ashes rose the modern American building code. By 1872, Chicago mandated fire-resistant materials throughout its rebuilt downtown. Brick, limestone, and terracotta replaced the pine and cedar that had made the city a tinderbox.

Chicago's response went beyond materials. The city established one of America's first building departments with real enforcement power. Inspectors could halt construction, require modifications, and deny occupancy permits. The modern plan review process was born.

Historical irony: Chicago's strict post-fire codes and innovative fireproof construction techniques made it a laboratory for skyscraper development. The disaster that destroyed the city created the conditions for it to pioneer the modern skyline.

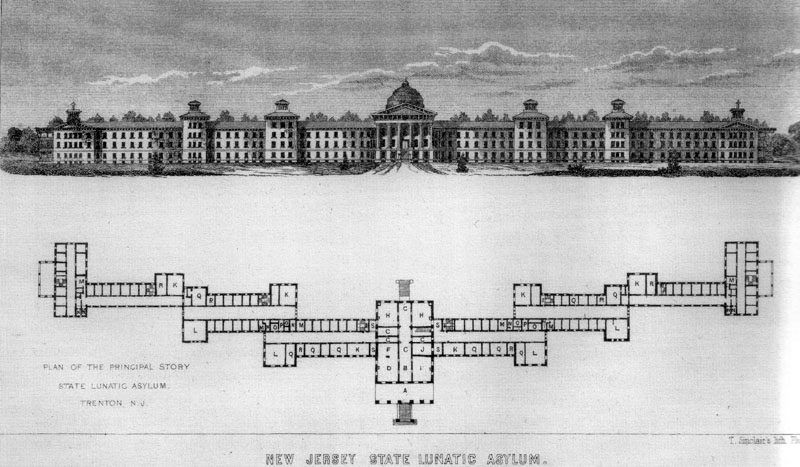

Part III: Building Departments Emerge

1865 – 1920

Having building codes meant nothing without people to enforce them. The late 19th century saw the birth of professional building departments—bureaucratic structures that transformed codes from paper promises into physical safety.

New Orleans becomes the first U.S. city to require building inspections

New York City establishes its Department of Buildings—still operating today

Chicago creates its building department in the fire's aftermath

These early departments faced enormous challenges. Plan checkers reviewed drawings by hand, measurements were verified with rulers and scales, and every permit required in-person visits. The workload was crushing, the tools primitive, and the stakes—as one tragedy would soon prove—literally life and death.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (1911)

March 25, 1911. A Saturday afternoon. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory occupied the top three floors of the Asch Building in New York's Greenwich Village. Inside, some 600 workers—mostly young immigrant women from Italy and Eastern Europe—were finishing their shifts.

At 4:40 PM, a fire broke out on the eighth floor. What happened next exposed every failure of the existing code system:

- ✕The single fire escape collapsed under the weight of fleeing workers

- ✕Exit doors opened inward, becoming blocked by panicked crowds

- ✕Stairwell doors were locked to prevent theft and unauthorized breaks

- ✕No sprinkler system. No fire drills. No alarm system.

146 workers died—most within 18 minutes. Many jumped from the 8th, 9th, and 10th floors rather than burn. Their bodies landed on the sidewalks of Washington Place.

The public outcry was immediate and sustained. Among those who witnessed the horror was a young social worker named Frances Perkins. Twenty-two years later, she would become the first female U.S. Cabinet member as Secretary of Labor under FDR, where she championed the laws that created OSHA.

Between 1911 and 1914, New York State passed 36 new laws regulating workplace safety. Requirements included:

Sprinklers

Required in factories above certain sizes

Exit Doors

Must open outward and remain unlocked

Fire Drills

Mandatory periodic evacuation practice

"The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire was the most dramatic episode in a long drawn-out fight for better working conditions. We saw the fire, we watched the victims leap to their death, and we knew in that moment that something had to be done."

Part IV: The Rise of Code Organizations

1893 – 1994

By the early 20th century, America faced a new problem: every city wrote its own codes. A builder working in Chicago couldn't use the same plans in New York. An architect licensed in California faced entirely different requirements in Texas. The lack of standardization created confusion, increased costs, and ultimately compromised safety.

The solution came through professional organizations that developed model codes—standardized requirements that cities could adopt wholesale.

Underwriters Laboratories (UL) Founded

William Henry Merrill founded UL after the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where electrical fires threatened the "White City." Today, UL tests products for safety compliance worldwide.

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Established

Originally focused on standardizing sprinkler systems, NFPA now publishes over 300 codes and standards, including the National Electrical Code (NEC) and Life Safety Code.

The Three Regional Codes

For most of the 20th century, the United States operated under three regional model code systems:

BOCA (1915)

Building Officials and Code Administrators

Eastern and midwestern United States. Published the National Building Code.

ICBO (1922)

International Conference of Building Officials

Western United States. Published the first Uniform Building Code in 1927.

SBCCI (1940)

Southern Building Code Congress International

Southern United States. Published the Standard Building Code.

This fragmented system created problems. Manufacturers needed to certify products under multiple codes. Architects needed different code expertise depending on project location. Plan checkers had to master whichever regional code their jurisdiction adopted.

The Great Merger: December 9, 1994

On this date, BOCA, ICBO, and SBCCI merged to form the International Code Council (ICC). The merger's goal was simple but ambitious: one unified code for the entire nation.

In 2000, ICC published the first International Building Code (IBC). Today, all 50 states have adopted some version of I-Codes, creating the standardization reformers had sought for a century.

Part V: The Tools of the Trade

1842 – 1990s

Before computers, before PDF viewers, before electronic plan submission, plan checking was a physical craft. The tools of the trade were simple, but mastering them took years. Every plan checker developed their own system—a personal methodology for catching errors that computers would later struggle to replicate.

The Blueprint Revolution

In 1842, Sir John Herschel discovered the cyanotype process—a photographic technique that produced white lines on a distinctive blue background. By the 1890s, "blueprints" cost one-tenth the price of hand-traced reproductions, making plan distribution practical for the first time.

The blueprint process revolutionized construction documentation, but it created a physical reality that defined plan checking for over a century: drawings were large, fragile, and difficult to mark.

The Art of Redlining

Ask any veteran plan checker about their tools, and they'll describe a system as personal as a chef's knife kit. While color conventions varied by jurisdiction—every building department had its own system—certain practices became widespread:

Red Pens & Pencils

The universal tool of plan review. Red marks indicated required corrections—items that had to be fixed before permit issuance. Architects called this process "redlining," and a sea of red on returned plans meant serious problems.

"I'm going to bleed all over these drawings." — Common architect expression

Yellow Highlighters

Yellow had a special property: it was transparent in photocopies. This made it ideal for marking approved sections or discipline checks—visible on the original but invisible on copies sent to contractors.

"Yellow for verification. It disappears when you need it to."

Blue & Green Marks

Secondary colors varied by office. Some used blue for back-checking resubmittals—verifying red corrections were addressed. Others used green for comments or deletions. Each jurisdiction developed its own system.

"Check the office manual. Every department has different colors."

Pencil Marks

Pencil served multiple purposes: personal notes, calculations, and tracking. Scrubbers circled completed items. Reviewers ghosted in potential solutions. Pencil could be erased—ink was permanent.

"Pencil is thinking out loud. Ink is the final answer."

The Plan Checker's Toolkit

Beyond marking tools, plan checkers relied on specialized instruments to verify dimensions and calculations:

Triangular Architect's Scale

Six different scales on one tool, allowing quick measurement of drawings at various ratios (1/4" = 1'-0", 1/8" = 1'-0", etc.)

Plan Wheel (Opisometer)

A small wheel rolled along curved lines to measure total length—essential for calculating egress path distances and piping runs

Light Tables

Illuminated surfaces that made tracing paper transparent, allowing comparison of multiple drawing layers simultaneously

Magnifying Loupes

For reading tiny text on reduced-scale drawings—essential when reviewing half-size or quarter-size plan sets

Rubber Stamps

"APPROVED," "REVISE AND RESUBMIT," "NOT APPROVED"—the final verdict came down with an inked thump

The Physical Reality of Plan Review

Consider what plan checking looked like in 1985. An architect submits plans for a three-story office building. The submittal arrives as rolled blueprints—perhaps 50 sheets, each 24" × 36" or larger.

The plan checker unrolls Sheet A1 on a large table, weighing down the corners with lead weights. They measure a corridor width with their triangular scale. They cross-reference the dimension against the code book—a thick, tabbed volume always within arm's reach.

Finding a violation, they reach for the red pencil. A note in the margin: "Corridor width 43". Min. required 44" per IBC 1018.2. Revise."

This process repeated for every sheet. A complex project might require 40+ hours of review time. The plans would return to the architect, who would make corrections on vellum, create new blueprints, and resubmit. Multiple review cycles stretched timelines to weeks or months.

"You developed a rhythm. Coffee in the morning, plans spread across the table, code book open, colored pencils lined up like surgical instruments. By afternoon, your back ached and your eyes burned, but you knew that building inside and out."

Part VI: The Digital Revolution

1982 – 2020

In December 1982, a small company called Autodesk released software that would transform the entire construction industry. AutoCAD version 1.0 cost $1,000 and ran on early IBM PCs. Within a decade, it had made the drafting table obsolete.

But CAD's impact on plan checking took longer to materialize. For years, architects designed on computers but submitted printed blueprints. The digital file existed, but the review process remained physical.

The Shift to Electronic Submission

The transition began slowly in the 2000s. Early adopters like Plano, Texas required electronic submission by 2009. The benefits were immediate and measurable:

Salt Lake City Results

- • 50% reduction in approval times

- • 360,000 fewer vehicle miles traveled

- • 512,000 fewer pounds of paper consumed

McAllen, Texas Results

- • Residential permits: 3 weeks → 3 days

- • Commercial permits: 6 weeks → 2 weeks

- • Customer satisfaction: dramatically improved

Yet digital submission created its own challenges. PDF markup tools replaced colored pencils, but the fundamental process remained manual. Plan checkers still read every sheet, still measured every dimension, still cross-referenced every code section. The medium changed; the methodology didn't.

Part VII: COVID-19 and the Digital Leap

2020 – 2022

When municipalities shut their doors in March 2020, building departments faced an existential question: How do you review plans when no one can come to the office?

Jurisdictions without electronic systems saw permit applications drop 50%. Construction projects stalled. Economic recovery depended on buildings that couldn't get permits.

The response was the fastest digital transformation in building department history. Practices that seemed years away became operational within weeks:

- ✓Virtual inspections: Arlington County, Virginia completed 4,000+ remote inspections in a single month

- ✓Online permitting: Jurisdictions launched systems in weeks that had been "planned" for years

- ✓Digital plan review: Teams collaborated on screens instead of around tables

COVID-19 didn't create digital plan review—but it compressed a decade of adoption into two years. Building departments that had resisted change suddenly had no choice. The future arrived faster than anyone expected.

Part VIII: The AI Era

2024 and Beyond

Building departments across America face a crisis that technology alone cannot solve: their workforce is aging out.

The Staffing Crisis in Numbers

85%

of code inspectors are over 45

30%

plan to retire within 5 years

50%

of institutional knowledge at risk

When a 30-year veteran retires, they take with them thousands of hours of pattern recognition—the ability to spot a problem before it becomes a violation, to catch errors that technically pass code but practically fail. Training replacements takes years, and there aren't enough candidates entering the profession to fill the gaps.

This is where artificial intelligence becomes not just useful, but essential.

How PlanCheckSolver is Transforming Plan Review

At PlanCheckSolver, we've built an AI system that augments human expertise rather than replacing it. Using computer vision and natural language processing, our platform performs the first pass of code compliance checking—identifying issues in minutes that would take hours to find manually.

Upload plans in PDF, CAD, or BIM format. Within minutes, AI highlights missing elements, flags potential code violations, and generates detailed compliance reports. Human reviewers then focus their expertise where it matters most: judgment calls, interpretation, and final decisions.

| Metric | PlanCheckSolver AI | Traditional Review |

|---|---|---|

| Code Issues Detected | 814 | 93 |

| Catch Rate | 97% | 11% |

| Review Time | 10 minutes | 8-10 hours |

Read the full case study: From Hours to Minutes: How AI Plan Review Cuts Timelines by 90%.

Conclusion: 4,000 Years and Counting

From Hammurabi's harsh justice to AI algorithms, the goal has never changed: ensuring buildings are safe for the people inside them.

Every advancement in building safety came from tragedy. London burned, and we got material standards. Chicago burned, and we got building departments. Triangle Shirtwaist burned, and we got workplace safety laws. COVID-19 closed offices, and we finally went digital.

Today, AI-powered plan review represents the biggest shift in the profession since the blueprint. But unlike previous advances born from disaster, this one comes from innovation—a chance to make buildings safer before the next tragedy, not after.

The plan checker of 2030 will work alongside AI assistants that catch code violations instantly, verify dimensions automatically, and flag patterns that suggest deeper problems. They'll spend less time measuring corridors and more time applying professional judgment to complex design decisions.

Hammurabi would approve. The goal remains the same. Only the tools have changed.

Timeline: Key Milestones in Building Code History

Sources & Further Reading

Historical Events

• Chicago Architecture Center: "The Great Chicago Fire of 1871"

• Museum of London: "The Great Fire of London 1666"

• Cornell University ILR School: Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Collection

• ICC Building Safety Journal: "The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire"

• Fine Homebuilding: "A History of U.S. Building Codes"

• NFPA: "Fire Safety 101: History of the NFPA"

Workforce Statistics

• ICC Workforce Development — 85% of code professionals over 45, 30% planning retirement within 5 years

• NIBS Town Hall Report: Future of Code Officials — ICC/NIBS 2014 workforce survey data

• PHC PPros: Building Code Professionals Face Labor Shortage

Digital Transformation Case Studies

• ICC Building Safety Journal: Arlington County COVID-19 Response — 4,000 virtual inspections in one month

Markup Conventions

• Eng-Tips Forum: Color conventions for engineering markup

• Life of an Architect: Architectural Redlines

Images

• Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

• Brisbane City Archives (Public Domain)

Related Reading

Top 10 Reasons Building Plans Get Rejected - Common issues with code references and how to avoid them

Building Plan Review Checklist - Complete guide for 2025

AI vs. Human Plan Review Case Study - See the data behind our 97% catch rate

Experience the Future of Plan Checking

From Hammurabi to AI in 4,000 years. See how PlanCheckSolver transforms plan review—catching more errors, reducing turnaround times, and keeping buildings safer.

Try PlanCheckSolver Free